Private HE is an indispensable part of the larger ecosystem

Article by Dr Linda Meyer

By educating more young people, South Africa can enhance its human capital, drive innovation and bolster its position as a regional knowledge hub. Yet, this potential remains largely untapped: hundreds of thousands of qualified South African youth are barred from higher education each year due to financial and capacity constraints.

The National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS), intended as a crucial support for disadvantaged students, is itself ensnared in administrative chaos.

Simultaneously, public universities can accommodate only a fraction of the demand. This article explores the pressing need to unblock the NSFAS funding pipeline, the structural pressures underpinning the access gap, the policy and political failures perpetuating the status quo, and evidence-based solutions to sustainably expand higher education access.

Massification has arrived

South Africa is experiencing a surging demand for higher education that far outstrips the capacity of its public universities. Each year, the number of school-leavers achieving a bachelor pass in the National Senior Certificate exam has been growing. In 2024 alone, roughly 337,000 matriculants earned bachelor-pass marks, qualifying them for university studies.

This reflects a broader trend of massification – as the country’s youth population grows and more families see university as the gateway to the knowledge economy, higher education has shifted from an elite pursuit to a mass aspiration.

Yet public universities can only enrol about 200,000 to 210,000 new undergraduate students a year. Government enrolment plans, limited infrastructure, and funding constraints have effectively capped first-year intake at this level, year after year. The result is a gaping chasm between demand and supply.

In 2024, approximately 127,000 qualified students had no seats at public universities. Each year, well over 100,000 capable young people are, thus, left on the sidelines – a “persistent pool of qualified but unplaced students” with dashed hopes.

This unmet demand has several immediate consequences.

Firstly, it has given rise to a parallel private higher education sector that is rapidly expanding to absorb those shut out of public universities. Private institutions now enrol over 20% of all higher education students in South Africa and have nearly tripled their numbers since 2010. Major private providers – from multinational college networks to specialised institutes – are growing at 6%-7% annually, far outpacing the stagnant public sector. This growth underscores the extent of latent demand beyond the public universities’ cap.

Secondly, pressure is spilling over to other parts of the post-school system. Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges and Community Education and Training (CET) programmes are facing rising enrolment requests as alternative pathways for those who cannot secure university places. However, these sectors have their own capacity and quality constraints and have not been scaled up sufficiently to absorb the overflow.

Policymakers thus face an acute dilemma: how to expand access for a growing youth population without overwhelming the system. The tension between widening participation and maintaining educational quality and financial sustainability is palpable.

For the past decade, the de facto approach has been to ration limited public university seats while offering NSFAS bursaries to a subset of students, a strategy now buckling under the dual crises of insufficient seats and inadequate funding.

The Access Gap

Several structural forces are intensifying South Africa’s higher education squeeze. Demographic trends are a fundamental driver: improved access to schooling has produced larger cohorts of matriculants eligible for tertiary study each year. Over 705,000 students sat the matriculation exam in 2024, with more than 615,000 passing – an 87% pass rate.

Compounding this is regional migration. South Africa attracts students from neighbouring countries in the Southern African Development Community, or SADC, region, as political and economic instability in countries like Zimbabwe and Namibia drives many youth to seek education opportunities in South Africa.

Economic inequality within the country is another structural factor. Extreme income disparities mean that many university-eligible students cannot afford higher education without financial aid; more than 556,000 candidates in the matric class of 2024 were beneficiaries of social grants.

Public funding limits form a hard ceiling on expansion, as higher education must compete with other pressing public needs amid slow economic growth, international pressure from the likes of the United States, and high debt-to-GDP ratios.

Fixing NSFAS

NSFAS was conceived as a lifeline for students from low-income families, but it has become a bottleneck stifling the system. Chronic administrative failures have led to repeated delays in disbursing student allowances, often leaving students stranded without food or accommodation and sparking protests that disrupt the academic calendar.

NSFAS disclosed to parliament that, in 2025, it is oversubscribed by ZAR10.6 billion (about US$606 million) for university education. These operational breakdowns are exacerbated by weak governance and frequent leadership changes, undermining ongoing improvement. Consequently, the scheme intended to widen access has become a source of instability on campuses.

Financially, NSFAS is unsustainable. The scheme now consumes nearly 36% of the entire higher education budget – about ZAR50 billion annually – yet still fails to meet student funding needs. Its funding allocation has grown explosively (from ZAR48.7 billion in 2025 to a projected ZAR53.4 billion by 2027) without evidence of improved efficiency.

Despite this massive expenditure, NSFAS cannot cover all eligible students: more than 615,000 learners qualified for higher education in 2024, but many went unfunded. Those most affected are the very students NSFAS is meant to help – youths from working-class and poor households, who are disproportionately harmed by delayed or denied funding. NSFAS’s loan book is plagued by rising debt and negligible recovery from graduates, indicating that the current model, essentially a grant for most recipients, is fiscally broken.

Governance scandals compound these issues. Persistent allegations of corruption, irregular tenders and maladministration have eroded public trust. Oversight is feeble: NSFAS has struggled to effectively monitor the private service providers tasked with disbursing student living allowances, leading to funds going missing or being paid late.

The systemic consequences are dire. The failure of this state-led funding model is undermining confidence in the government’s ability to deliver on its education rights commitments. It also exacerbates inequality (only students with other means or exceptional persistence can survive the funding shortfalls) and fuels instability as frustrated, debt-burdened youth take to the streets – as is the case at the University of Fort Hare.

Moreover, NSFAS’ failures push thousands of unfunded students towards private colleges or the labour market, highlighting the fragility of the public system and shifting the burden to families or private institutions. In short, fixing NSFAS is a first-order priority: without a functional student aid system, expanding access will remain an empty promise.

Growth in private providers

The rapid expansion of South Africa’s private higher education sector represents one of the most profound shifts in the country’s post-school landscape since the dawn of democracy. In less than two decades, private higher education institutions (PHEIs) have evolved from niche providers serving a small professional market into a substantial and growing component of the national higher education system.

Whether the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) embraces it or not, private higher education is now an indispensable part of the larger ecosystem, absorbing unmet demand, diversifying access pathways, and increasingly shaping national skills.

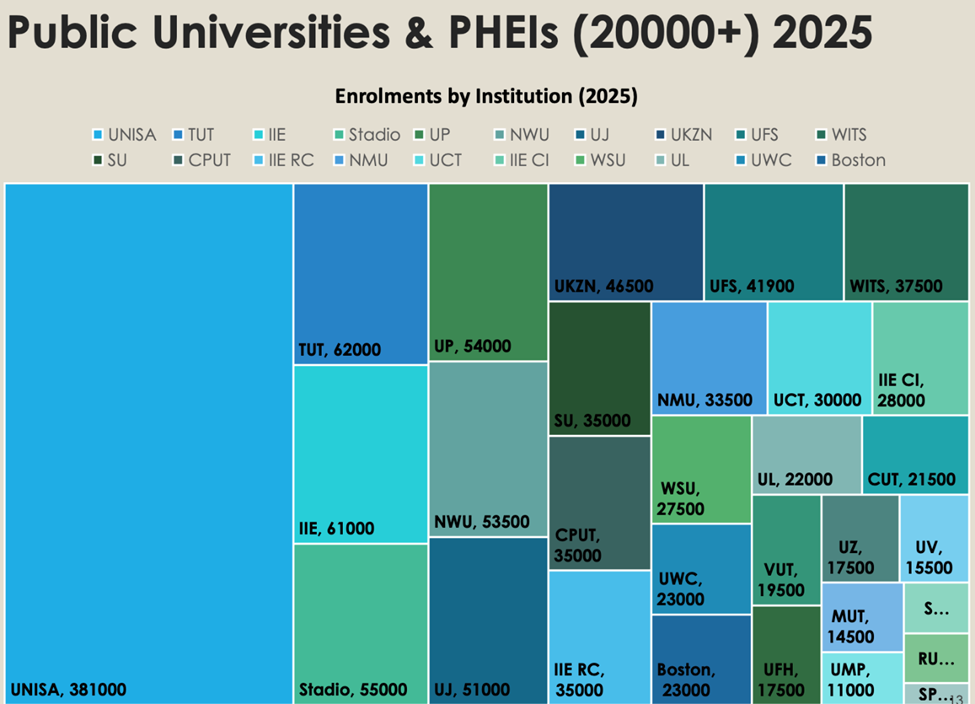

The empirical evidence is striking. Between 2010 and 2023, PHEI enrolments almost tripled – from 90,767 to 286,454 students – reflecting an annual growth rate of around 6%-7%, compared to the public university system’s near stagnation in total enrolments, which have plateaued at roughly 1.07 million since 2017.

At this pace, and, assuming modest public institution expansion, projections show that private higher education could surpass the public university system in total enrolments between 2045 and 2049. These figures challenge the long-held assumption that higher education is, and must remain, predominantly a public endeavour. Instead, they reveal a structural rebalancing of the system. It is into this vacuum that private institutions have stepped, often more agilely and responsively than their public counterparts.

PHEIs have grown, not only in numbers, but also in diversity and sophistication. Once dominated by business colleges and teacher-training providers, the sector now spans a wide range of disciplines, from commerce and education to emerging STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and digital fields.

The Independent Institute of Education (IIE), Stadio, Boston City Campus, Eduvos and SANTS collectively account for the bulk of private enrolments. Still, a growing number of smaller, niche providers now target professional reskilling, micro-credentials, and distance learning.

The demographic profile of PHEI students also contradicts stereotypes. Nearly 70% are black African, and a significant proportion are first-generation tertiary students. Importantly, PHEIs also attract older students, including those aged 25-38, reflecting a broadening market for lifelong and flexible learning.

In essence, the DHET’s planning frameworks have underestimated the role of the private sector, both as a pressure valve and as a legitimate partner in advancing national development. The stubborn reality is that fiscal ceilings have constrained the public system’s growth: the DHET’s budget has risen nominally from ZAR137.5 billion in 2024-25 to an expected ZAR158 billion in 2027-28, a 4.8% compound annual growth rate that barely keeps pace with inflation.

Real per-student expenditure in public universities remains static, while the number of eligible applicants continues to climb. This makes the contribution of private providers indispensable, even if policy discourse on PHEIs remains confused.

Beyond filling numerical gaps, PHEIs are altering the functional logic of higher education. They are less encumbered by the bureaucratic and infrastructural inertia that constrains many public universities, allowing them to pivot more quickly to market and technological demands. Many have invested heavily in digital platforms, blended delivery, and partnerships with employers – precisely the kind of flexibility the DHET and Council on Higher Education have long urged the public system to adopt.

They also offer entry-level higher certificates and stackable degree pathways that expand participation among students who might otherwise be excluded. Their responsiveness has made them essential engines for workforce development in business, education and applied technology.

While private tuition fees are generally higher than public ones, many institutions offer bursaries, flexible payment structures, and corporate partnerships that make access feasible. Moreover, NSFAS’s chronic dysfunction has further reinforced the legitimacy of alternative, market-based models.

Whether policymakers like it or not, the binary between ‘public’ and ‘private’ higher education is increasingly obsolete. South Africa’s higher education ecosystem is a single, interdependent system characterised by both competition and complementarity. Public universities, PHEIs, TVET colleges and CET centres form a continuum that must be integrated through articulation frameworks, shared quality assurance, and equitable funding mechanisms.

The DHET’s insistence on treating private providers as peripheral risks undermines national human capital objectives. Instead, policy must shift towards coordinated expansion – recognising private institutions as legitimate partners in achieving enrolment, throughput, and employability targets.

The rise of private higher education in South Africa is not an anomaly but a structural response to the inefficiencies and constraints of the public system. Its growth embodies the adaptive logic of an evolving post-school ecosystem, where the boundaries between state and market provision blur in the pursuit of access, quality, and relevance. To continue denying its role would not only be futile, but counterproductive to the broader developmental mandate.

Expanding access

Expanding access to higher education necessitates ambitious, evidence-based reforms across multiple fronts. This includes restructuring NSFAS and forging student finance partnerships to enhance capacity, innovate delivery modes, and implement key interventions.

An overhaul of NSFAS is essential, transforming it into a decentralised, financially sustainable system. Functions should be reallocated to universities and TVET colleges for closer oversight of qualifications and fund disbursement. Portable grants or vouchers would enable students to attend any accredited institution. An income-contingent loan recovery mechanism, whereby graduates repay a portion of the funding once employed and earning above a threshold via the tax system, mirrors successful models in Australia and the United Kingdom.

This approach eliminates inefficiencies, curbs corruption, strengthens accountability, ensures financial sustainability, and shares costs between the government and graduates. Over time, this will support more students and restore some degree of trust – a prerequisite for broader access expansion.

Public-private partnerships are crucial for increasing capacity. Collaborating with the private sector can build on the trend of public-private collaboration through work-integrated learning placements, co-developed programmes, and articulation agreements. Contracting private institutions to educate students with public funding, purchasing seats, and co-investing in infrastructure are key strategies.

Government grants and guarantees can help private and community organisations establish new campuses in underserved provinces through revenue-sharing arrangements, leveraging private capacity for rapid expansion with minimal state investment while ensuring quality is monitored.

Adopting blended and flexible learning models is another vital strategy. Embracing educational technology can stretch existing capacity and increase access. A hybrid model for large first-year courses taught partly online can significantly reduce the need for brick-and-mortar expansion. Modernising distance education platforms like UNISA [the University of South Africa] to serve working adults in remote areas will improve success rates and open doors for those lacking campus access. Investment in connectivity and devices to bridge the digital divide is critical for stability.

An integrated Post-School Education and Training (PSET) ecosystem that enables movement between institution types is also necessary. Strengthening articulation and credit transfer mechanisms will absorb more students in the short term, ensuring talent isn’t wasted.

Incentivising alignment between funding and qualifications frameworks will reward institutions that receive transfers. Central application systems can redirect overflow applicants to alternative institutions, spreading the burden of expansion across different institution types and creating more opportunities within the PSET ecosystem.

Investing in infrastructure innovation is unavoidable to close the gap. Upgrading existing facilities through efficiency grants, adding teaching venues, student housing, and labs, implementing energy-efficiency retrofits, improving labs, addressing maintenance backlogs, and implementing load-shedding contingencies are critical for stability.

Innovative approaches like sharing facilities or deploying mobile “pop-up” campuses focused on high-demand fields with specialised facilities can yield significant benefits. Public works programmes building education infrastructure will create construction jobs while expanding capacity for future generations.

Unlocking access to higher education requires breaking away from incrementalism to address deeply entrenched problems, such as an overwhelmed NSFAS and vast supply-demand gaps. Structural inequities are not insurmountable; bold reforms pursuing a reimagined student funding model, cross-sector partnerships, and modernised delivery modes can make real progress towards an inclusive, high-quality system.

Costs of inaction

The payoffs are far-reaching: empowering thousands more young South Africans with skills and degrees will boost the nation’s economy through increased productivity and innovation. Educating youth from neighbouring countries will strengthen the geopolitical standing of the region as a regional hub, helping address Africa’s development challenges.

The cost of inaction is lost potential and social instability. It is time for a coalition of government, academia, industry, and civil society to drive forward the changes needed to expand access and realise this vision of sustainable growth.

In a landmark development for South Africa’s tertiary education landscape, the DHET officially gazetted the Policy for the Recognition of South African Higher Education Institutional Types (Government Gazette No 53515, 17 October 2025).

This pivotal policy reform allows private higher education institutions that meet the required academic, governance, and quality standards to be formally recognised and designated as universities or university colleges.

It marks the culmination of years of advocacy, policy refinement, and national dialogue on the equitable treatment of higher education providers in South Africa’s dynamic, evolving post-school education system. For the first time in South Africa’s democratic history, private universities can rightfully be called universities.

The promulgation of this policy signifies a victory for academic legitimacy, institutional equity, and the evolution of higher education in South Africa. It acknowledges that quality education transcends ownership boundaries and is a public good delivered by both public and private entities committed to advancing society. The door has finally opened to a future where collaboration, innovation, and excellence define the university experience across all sectors.

Dr Linda Meyer is managing director of IIE Rosebank College. This is a summation of her keynote address given at a Council on Higher Education Colloquium held on 18 September 2025. The subsequent developments have been added as a solution-oriented move for the good of the higher education institutions and economic growth.

This article is a commentary. Commentary articles are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of University World News.

ADvTECH Updates